Indonesian collector Wiyu Wahono is a great connoisseur of art history, an avid reader, and most importantly, a keen observer of how societal changes influence art. He is well aware of the need to know about art history in order to orientate oneself in the meanderings of contemporary art. In his view, to collect the right work, you need to understand the spirit of the times; what the Germans call the zeitgeist.

Interview : Selina Ting

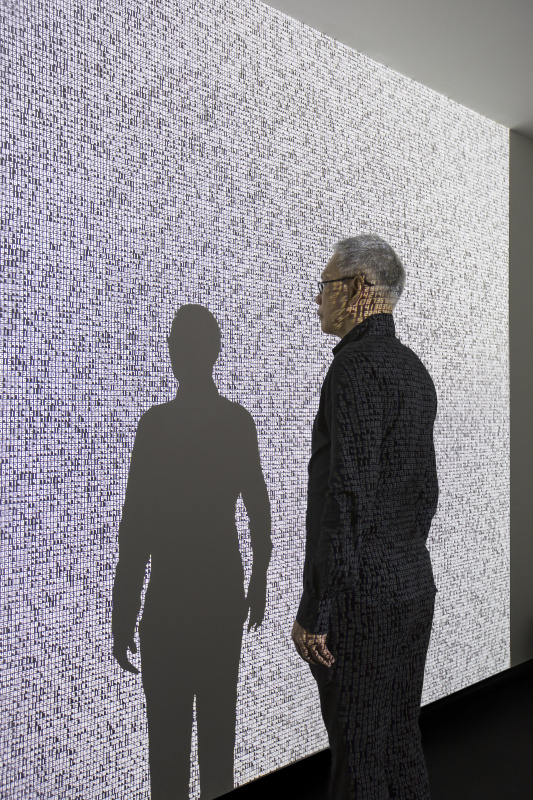

Images : Courtesy of Wiyu Wahono

Original Text published on COBO Social on 9 August 2017. Courtesy of COBO Social

Part 1: The beginnings and modernism

The original story of Indonesian collector Wiyu Wahono is tied to a seminal trip he took to Venice as a young twenty-something. Following the instructions of his tour guide, he visited the Peggy Guggenheim Museum, where he saw his first Jackson Pollock.

“It was one of the works from his early period, which was composed of monochrome and black paintings. I was confused and I didn’t like it. I compared it to the Indonesian art that I was used to, which was very colourful. At that time I asked myself, why do these paintings deserve to be in a prestigious, must-go museum?”

However, as often happens in the most romantic love stories, something happened after that rejection which changed the future collector’s mind. “I was a student, maybe 22 or 23 at that time. I saw a painting by László Moholy-Nagy, a composition. It was love at first sight. It blew me away. I bought the poster and hung it up in my small apartment.”

From there, he started going to exhibitions and learned to appreciate art. When Wiyu finished his studies in Germany, he started working as a state employee in a university. One day, during a holiday to Bali, he bought his first painting.

“It was around the end of the 80s. I didn’t consider myself to be a collector back then. I bought some paintings to decorate my apartment, but I didn’t formally collect. Then, later on in 1997, I came back to Indonesia and started my own business. It was running well and I had more money, so I thought I could finally start collecting.”

What was that first piece that you bought in Bali?

The first piece was by Teguh Ostenrik, an artist who studied art in Berlin. I knew him by name and his works had been collected by German museums. When he moved back to Indonesia, nobody understood him, as usual. I looked for him and bought my first piece around ’99 or 2000. Today, I regularly buy his artwork. He is a very intellectual artist.

Is there a particular kind of artwork you focus on?

If you come to see my collection, you will see I’m against medium specificity because I want to show the freedom that comes from using different media to make artwork.

In the era of modernism, art has to be medium specific. Medium specific means that if an artist decides to do a two-dimensional artwork, it has to be on canvas, or if you choose to make a three-dimensional artwork, it has to be a sculpture. You don’t have a chance to do other things. That’s why if you open a Western art history book, it’s only about paintings and sculptures. As I see it, artists were put into straitjackets. They couldn’t move. In the second half of the 50s, Robert Rauschenberg started making the so-called combine – a canvas with objects on top. That was against medium specificity. Claes Oldenburg produced The Store. It was three-dimensional artwork, not a sculpture.

If an artist comes to me saying he has a very nice painting, the first question I will ask is: “Why painting? Are you still sleeping? Don’t you know that the straitjacket doesn’t exist anymore?” And then, if he answers, “Oh, yeah, but my context, the idea, the message I want to convey can only be done in a painting,” then that is okay. If you give me a plausible explanation, then I will collect.

Indeed, the scene in Southeast Asia is still predominantly painting, even though there are artists doing more experimental work.

Yes, still, and so the market is full of paintings. I think this is because of a misunderstanding. Most of the collectors don’t read. If you ask people, “Why do you collect?” they say, “Because I like it.” The topic of medium specificity is not discussed publicly, only in good books.

What do you think of digital art and so-called post-internet art these days?

It is interesting to me. I was collecting a lot of video art when nobody else was doing this in Indonesia, but I don’t want to be a video collector only. I think that when you see a painting in a museum or art space, you have full control of how long you stay and see the artwork. The problem with video art is you stand there and feel like you have to see the whole thing. However, if the video is 20 minutes, you cannot stay that long. After a while, you feel like you need to go. Otherwise, you won’t have the chance to see the other things in the museum. When you move on, you feel like you don’t have any control anymore. You get frustrated because you feel you don’t understand it yet. It’s crazy.

Another interest of yours is the boundary between fine art and applied art. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Traditionally, universities had fine art departments to distinguish themselves from mass culture. You can still call both fashion design and car design art, but you can’t call them fine art because they have a function, whereas fine art has none.

This boundary dissolved in post-modernism. When Andy Warhol exhibited his ‘Brillo Box’ it was a thing that every American had at home. He was so impressed by it that he produced an artwork, according to the consumer society of that time. Arthur Danto, the most influential philosopher back then, came and asked, “Why is this Brillo box art, and the Brillo box in the 7/11 supermarket is not? Visually, they are exactly the same.” You could argue that the first was signed and produced by Andy Warhol, an artist, while the latter was produced by factory workers. However, in reply to that objection, Andy Warhol remarked that he didn’t make the Brillo boxes himself. Warhol was very smart.

Arthur Danto concluded that visually you cannot see any difference between art and non-art. He also said there are no boundaries and definitions in postmodern art. To him, what made an object become art was not visible, so you could not say something was art because it had a nice colour. So, because there is no definition, the boundary between fine art and applied art has ceased to exist nowadays. Craft can be art.

Andy Warhol’s approach to a mass-produced object is different from Marcel Duchamp’s. Duchamp’s urinal was not made by the artist. Therefore, it was the idea, as well as who chose the artwork, that represented the art. In other words, this urinal shifted to become conceptual art, in which the idea is the artwork. We know that America became industrial after the Second World War and very successful because the whole world bought from them, so all their rich guys started to collect and buy everything. The artists didn’t like the fact that only the rich could appreciate art and buy it, so they tried to find a solution. What they came up with was to make art immaterial. To make it a concept, so it was no longer an object.

Do your reflections on art history influence your way of collecting?

Yes, they shape it. I’m very systematic, not only in the way that I think, but also in the way I collect. I can tell you why I see every artwork in my collection as being contemporary, and also from which point of view. For example, I have a painting of Osama Bin Laden that is handcrafted with markers. This is contemporary art in the spirit of the times.

Another thing that shapes my collection is the fact that my parents came from China, Guangdong. I was born in Indonesia as one of the so-called TCK, third culture kids, who were multicultural and open-minded. Then, I moved to Germany and was confronted with a new culture again, which I think brought about another layer of understanding about identity into my subconsciousness. It ended up influencing my way of looking at globalisation and the importance of context in understanding an artwork.

Can you go a little deeper into why context is important in the understanding of contemporary art?

We know from art history that conceptual art couldn’t survive because it was so difficult to understand. People started talking philosophically about art. You had to be overly intellectual to understand conceptual art until today. Now, the concept is not an issue anymore in postmodernism and contemporary art. We are not talking about the idea of an artwork, but the message of the artwork. In order to understand it, you need to look at the context.

Arthur Danto wrote about a very interesting fictive exhibition, the so-called ‘Red Square’ exhibition, where all the artists submitted a red square as an artwork. It was exactly the same red square. The first artist, who was from Russia, said, “Oh, this is the Red Square in Moscow. There is the Kremlin, which dictated everything that happened in the Eastern Bloc. This is my Red Square”. Another red square was by an Israeli artist, who said: “This red square is a metaphor for the Red Sea where Moses travelled and where the sea split.” So the red square for him was a metaphor for the biblical story. The other one was French and he said, “Oh, this red square is a homage to Henri Matisse, who made the red room painting.” So, formally, all the red squares aren’t the art per se. What makes the same object become a different artwork visually is the context. I feel this is the key to reading contemporary art nowadays.

Part 2: Approach to collecting and Indonesia

Having lived in Berlin for 20 years, Indonesian collector Wiyu Wahono is quite familiar with the German word zeitgeist. However, when he went back to Bali, he realised that people were not familiar with this concept in the realm of contemporary art. He noticed that the art world was stuck in a painting style that belonged to the past.

“When I started going to galleries in Indonesia, I realised that I couldn’t learn much. At the time people were paying $30,000 for Arie Smith, a Dutch artist living in Bali, who did impressionism. I was thinking, impressionism in the 20th century? $30,000? That is crazy!”

Wahono believes that even if you can understand what kind of art reflects the zeitgeist, you can never be sure about what it embodies. At least not in the present: “You will have to wait 50-100 years from now before you will be able to tell. Only then will a collection conforming to the zeitgeist finally appear as a good one. That’s why it is an intellectual challenge to find out what will be seen as the zeitgeist of today and buy the artwork that relates to the significant zeitgeist. In 1989, for example, I saw globalization and movements of people, the hybridity of culture and the issue of identity as part of the spirit of contemporary art.”

Are artists more sensitive to this idea of zeitgeist compared to collectors?

Artists lead the way; museums, collectors and art dealers only follow. Artists need to have the sensitivity or intellectuality to reflect the zeitgeist. Of course, collectors need to have the knowledge and look for artwork that reflects the zeitgeist.

For a collector, the big challenge is to say no to an artwork that you like. This may leave many perplexed and it is really difficult to do. You see an artwork and perhaps it’s emotional for you because it relates nostalgically to a past period. Every time I see a certain kind of work, I always go: “Oh, this reminds me of the 80s and 90s.” However, if I can afford to buy it before proceeding, I first reflect on the impact it will have on my collection. I don’t want the collection to become incoherent. There are so many people in the world who have spent so much money to collect art, but they are not listed among the ‘great collectors’. The reason is they have created a collection that is too eclectic. Certain people are not coherent.

You read a lot, does this inform your collection?

I read every evening before I go to sleep. It was from reading books that I realised the sense of contemporary art is about the context. There are several spirits of contemporary art that I have learned from books. I am very systematic in my readings. It’s an illness. So, I read books and made a conclusion about how to use the information for my collection. I have to pay attention in order to make my collection stronger. This is my approach and those who come to see my collection instantly see it and feel it.

Do you read mostly art books?

I also read books regarding art economics. This is because a lot of young people who come to me want to invest in art and ask me for some hints. I can’t give them direct information because I’m not investing in art. So I go to people who study art economics and ask them for book recommendations. Then I’ll buy what they suggest on Amazon. This way I can give people some quality information that will be useful to them as investors. I’m able to give them a couple of the books that they can read to start investing in art.

Do you generally consider art to be a safe investment?

If you do it right, yes it is. I know a big art investor in Indonesia who makes plenty out of art. A lot of people get mixed up about investment. They buy a painting for $100 or $10,000 and then sell it for $15,000, but that is not an investment as they are art dealers, not investors. Art investment is the same, whether you have $100 million, $10,000 or whatever. The real investor will say, “Okay, usually investors diversify their portfolio and I will buy 10% stock, 50% US Dollars, 10% gold and 15% property and land, and 15% art.” Every asset class has to bring a certain return that is, of course, higher than the bank interest. Then you manage your artwork in the moment. When the price rises, you have to sell because this profit will enable the portfolio to perform in the same way as the other asset classes. That is investment, not buying and selling. A lot of people say, “Oh, but I lost last time. I bought it for $400 million and now it’s only $15 million,” but this is not what we are talking about in investment. The real investor is doing what I said. If you do it right, art is a good investment, according to some people I have met.

Are there more and more young art investors?

I don’t really know because they are so shy, they don’t want to be exposed. They present themselves as collectors, but if you listen to them for 10 or 15 minutes, you realise they are only interested in the money. I know one person who openly admits to investing in art and he has one of the biggest wealth management companies in Indonesia. When I met him the first time, I saw his collection at his home, which included a few Damien Hirst’s. He says he treats his portfolio exactly like every asset class, like gold and others. It’s so funny. I invited him for dinner with a lot of young collectors and asked him if it ever pains him to sell the art he loves. He coldly said: “No, I just sell.” It was shocking! So crazy!

Are you one of the most outspoken collectors in Indonesia?

I think so. A lot of people hate me. I have lived in Germany a long time and Germans are very straight talking. They just say what they think. However, when people ask me what I think of a show that I don’t like, I always try to motivate my position, so the artist can learn something and next time he can do better. Artists must realize that when you exhibit an artwork in a public space, it becomes the public domain. You have to accept that there will be people who like it and people who don’t. You cannot filter the reactions and only have people say good things about the art. It’s not possible.

Are you still doing the art lovers dinner with young collectors?

I do. That is what I do in Indonesia. The art lovers’ dinner brings together friends and new collectors to sit together and discuss certain topics. Not regularly, but once in a while. We often talk about what we have bought and new ideas. In other countries, there is competition among collectors but we don’t have that in Indonesia.

What is the difference between owning a piece and going to a museum to see the work?

I like to see private collections more than museum shows actually. I think a collection reflects the collector’s personality. Whenever I see a collection, I always think: ‘What kind of person is he? What was in his mind when he bought these works, and what is the relationship between them?’ From there, I can suppose that he is, say, a very sentimental or emotional collector, even if he’s not present. This is always what challenges me. I want people to come to my office, see my collection and guess my personality if I am not there.

Some art pieces displayed in your office pretty much dominate the space. What effect does showing this very intimate side of yours have on clients?

It doesn’t help the business at all (laughter). On a personal level, every time I go to work I pass the art and I can enjoy it. When clients come in they always think it’s a graphic design office. If I have the chance, I take the time to introduce them to all the artwork a bit. I tell them I collect contemporary art and get a feel if they are interested at all. If they are not, then you skip it. Anyway, I think the office looks good, whether the clients like art or not.

I also think that having art in the office helps with our branding, as people feel like, ‘This is another level.’ I mean, I’m selling German plastic bottle blowing machines. Perhaps people who come to my office feel we have another level of sophistication and so the machines must be good. At least, I hope so. I don’t know whether it works or not (laughs)!